New beekeepers

What you need to get started

So you’ve decided to become a beekeeper? That is great news! This section is for new beekeepers. Welcome to the apiary.

Your decision to become a beekeeper and raising bees has been gnawing at you for years, I imagine. I know it did for me, and for me it has turned into a nice sideline business, I might add. I remember when I made the plunge. There was so much to read, so much information to soak in. I had to learn biology, virology, botany, and, of course, beekeeping. While that might seem like a lot, and perhaps at times overwhelming, there are a number of things you can do in preparation for your first colony.

I recommend two things to all new beekeepers: Find a mentor and have at least two colonies to start with. A mentor is an experienced beekeeper that can guide you in the nature of honeybees. Ideally, the mentor should have at least 5 years of beekeeping service. As with mostly everything in nature, there are patterns to look for: patterns of colony propagation, nectar flows, reproduction, dearth, illness, pestilence, and more. Once you understand the patterns does beekeeping become productive. It’ll take you a few seasons (years) to become proficient. You might be overwhelmed from time to time, and every new beekeeper will generally have the same questions. This is what a mentor is for (and if you buy bees from us, I am always a text or call away to answer your questions). The reason I recommend two colonies is because it is very difficult to recognize if a single colony is performing poorly if that is all you have (symptoms indicative of pestilence, disease, a failing queen…etc.). Two colonies can give you an expectation of what a baseline colony should look like. If one is taking off and the other is not, well, then you have something by which to recognize that.

Besides ordering your nucs (a nucleus colony), you need equipment. A nuc is a 5 frame “starter” that has brood, nurse bees (young bees), some food (pollen, nectar/honey), and a queen. You will likely get your nuc in the spring and since that is when honey bee biology dictates colony build-up, they will quickly outgrow the nuc box and, much to your dismay, swarm off. You need to have the right equipment on hand to grow your hive (the hive is the structure the bees, or colony, lives in) or reduce the hive depending upon the colony’s needs. Below, you will find a list of recommended equipment and the relative price for it. A word of advice here: NEVER buy or use used equipment. There is a disease called American Foulbrood (AFB). The spores of this disease can live for many years in used equipment. If AFB is found in your colony, the only prescribed treatment is to seal the hive with the colony inside and burn it. The disease is that severe.

In Florida, beekeepers must register their apiary (hive) with the state. You may do so by clicking here. Once you receive your nuc(s). A state apiary inspector will visit you to ensure that your colony is set up properly and is free of disease. The inspector is not there to harass you, and I believe you will find them very knowledgeable and eager to help. The inspector’s main purpose is to ensure your colony is not Africanized and is free of AFB.

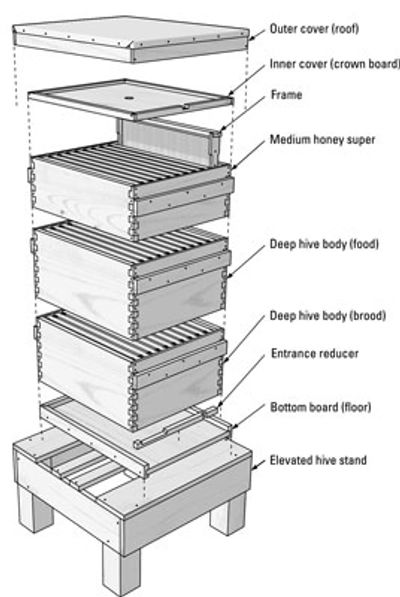

You will need to select the type of hive components. There is a list below, with the purpose of each item, and a relative price (some places are higher, some lower). Order these before your nuc arrives as you will have to assemble them and protect them from the elements. I use white oil based exterior paint (from any of the box stores) with a gloss finish (I am particular to enamel). A note of special concern here is the only surfaces that you should paint are the exterior surfaces. The bees need the exposed wood inside the hive to regulate the temperature/humidity inside it. Sealing the interior of the hive in paint may very well doom your colony. The Florida sun and rain are very harsh on wooden components. Using pine wood is the most common, and protected properly will last you many years. Another excellent choice of wood is cypress. Cypress has natural oils in it that help to protect against the harsh conditions here in the South.

A search online for hive components and equipment will turn a lot of results. I use two places to order my equipment. Mann Lake Ltd. is a national supplier with very competitive pricing. The benefit of Mann Lake is that for most orders over $100, they ship for free. I order equipment on pallets and its delivered by semitruck, and I pay zero-zilch-nada for shipping. We also have Full Moon Apiary in Monticello. Operated by a master beekeeper, it offers a decent selection of equipment for immediate pick-up. Some of the prices might be higher, but the benefit here is that you drive out and go home with whatever you need. Plus, Full Moon is local and it is always nice to support local businesses.

There are two forms of pests that I think I should mention to you at the very onset of your adventure: varroa destructor and the small hive beetle (SHB). Varroa, or as most be call them, “the mites”, are very small ectoparasitic mites that feed on the fat of honey bees (click here to watch a video by Dr. Jamie Ellis of UFL's Department of Entomology and Nematology). Varroa, in and of themselves, will not kill a colony, although they will weaken it to the point that something will kill it or it will abscond to try and find relief. What makes varroa so important as a pest is that it is a vector. Vectors carry disease, and the diseases of varroa are many. There are a number of treatments that are very effective against varroa, and some of these include Apivar, oxalic acid, thymol, and a few others. Since honey bees create a human food, treating honeybees when the honeycomb box (called a super) is on is against the law. That leaves us July-February to cull varroa. Apivar is probably the easiest method for new bee keepers to use, and you’ll want to bear that in mind.

The SHB are what we tend to consider as a secondary pest (watch this educational video by Jamie Ellis of UFL). Once the colony weakens, the hive beetles move in en masse. These little creatures have a hard exoskeleton that is impervious to bee stings, and therefore, the bees cannot rid the hive of them. There are traps that we use, and you will see that appear in the list below. I use 6-8 per box (if you have 3 boxes for one hive, then you are putting out 15-18 traps). The directions indicate that the traps are to be filled with oil, and maybe some vinegar, and placed into the hives. The bees chase the beetles around, with the beetles finding refuge in the traps – only to drown. I use diatomaceous earth in mine instead. The reason for this is because little rotting hive beetles simmering in oil in the Florida summer tend to create a nasty stench. Since the diatomaceous earth desiccates the beetles, there really is no smell. SHB likes a rich protein diet, and it just happens to be that pollen is high on their list of yummy snacks. The beetles will lay eggs near the pollen and nectar (nectar is honey that has not yet been evaporated and sealed) and shortly thereafter the eggs will hatch. The larvae eat their fill, go through the instars, then wiggle out of the hive, dropping to the ground. While burrowed in the ground, they pupate (turn into adults), emerge, and the cycle repeats. The larva, while in the hive, secrete a yeast that sours the honey and other bee food, rendering it useless to the colony. A strong healthy colony will be able to keep the SHB under control along with your help via the traps. I tell you this now, so you don’t fly into panic mode next summer.

Here is the equipment list I promised you: For each of your colonies, you will need a hive. The most simplistic hive is a bottom board, (1) deep chambered brood box, frames, and a cover. This simplistic design won’t allow you to collect honey, though. The deep chamber, or bottom box or two, is where the colony does its magic at. This is where the queen lays her eggs, the bees tend to the young, some food is stored, and should be regarded as the central aspect of the colony’s vitality. Some beekeepers like to use only one, whereas others like to use two. The difference between them is in a healthy, established colony, the second box permits a larger population. A larger population is able to bring in more nectar. Honey supers only go on about 2-3 weeks before the nectar flow (see the calendar section) and usually come off mid-summer when the dearth is upon us. Between the supers and the deep boxes is a queen excluder. This is designed to be just the right size to allow the workers to access the honey supers, but not the queen. This prevents her from laying up there and the result is the golden honey and light-colored comb you are expecting. If the queen were to lay in the supers, the pupating larvae leave behind cocoons that overtime stain the wax dark, even black. The inner cover can be multifunctional, perhaps providing for some head space, aid in ventilation or air flow, and keep your bees from sealing the outer cover to the top box with propolis.

You will hear of 10-frame and 8-frame hives. It matters not what you pick, but once you do, you are kind of married to it. As the name implies, a 10-frame hive holds ten frames. This is space for 1500-2000 more bees than an 8-frame box. More bees = more production. In my opinion, the main consideration is the weight of the boxes when lifting. Personally, I only use 10-frame hive materials.

A last thought on hive materials. You will see that most suppliers sell 2-3 grades of material: budget, commercial, and select. Select has the least knots in it, whereas budget has the most. Whatever you buy, once you assemble the boxes, be sure to work in a caulk into the finger joints and all exterior knots/cracks before you paint. I assemble all of my boxes and seal anywhere I think the weather may get in (I don’t want my boxes to rot!) with caulk. I wait for the caulk to dry, then I hit the joints with my belt sander. This smooths the rough joints and allows me to look for any spots I may have missed before I put my nice oil-based exterior paint finish on.

So, for each colony that you want you should have:

A bottom board. Going price is $11-21 with the reducer (get the reducer!)

Deep hive bodies (9 5/8”). You will want 1-2. Going price is $11-16

10 deep frames for each of the deep hive bodies. Going price is $11-17 for a 10 pack

10 deep foundation for each of the deep boxes*. Going price is $12-18 for a 10 pack

Queen excluder (just 1 per hive). Going price is $4-18. I use the metal ones ($7-8 a piece)

Honey supers (either medium 6 5/8 or shallow 5 5/8). 1-2. Going price is $9-12 for either.

For each super, 10 frames that are the same as the super (medium or shallow). Going price is $11-17 for a 10 pack

An inner cover. Going price is $15-21

An outer cover. Going price is $30-35

Foundation is usually a preprinted plastic or wax base for the bees to draw (beekeeper for make) the comb upon.

Beetle traps (remember, 5-6 per box. Some people say 2-3, but I find the more, the merrier. Shop around for the best price). Going price: about $1-2 per trap. Some stores sell bulk discounts.

Personal and protective equipment (PPE)

A smoker (this keeps the bees from communicating the alarm, or sting, pheromone). Going price is $30-50. (Ps. Don’t buy smoker fuel. It’s a waste money. Use pine straw).

A veil (I cannot stress this enough. A sting to your eyes will surely result in blindness). Going price is $19-52

A hive tool. These are ok to buy from Amazon (the cheap ones are Chinese). Grab a couple of them. You’ll thank me later.

These are the absolute minimum REQUIRED gear. A couple of puffs of pine straw smoke will really aid in maintaining a gentle disposition while you are in the hive. Still, you might get stung, hence the veil requirement. Some people also elect to wear the following:

A bee jacket. About $75 for a nice one

Kid leather gloves $12-25

Bee suit $60-174

A note on buying equipment, from my personal experience: It is tempting to go online to Amazon and buy the cheap equipment. For some items, like the hive tool, that is fine. I would strongly recommend you not do so when purchasing your smoker and veil. The smoker will take a beating from you. You are constantly using it. It gets bounced around. It gets hot, cold, wet, dry. You get the picture. The bellows of the cheap Chinese knock offs will rarely last one summer. So, while you may see a smoker online at Amazon for $15-20, be prepared to buy one of those every year. Or, you could spend $40-50 once at Mann Lake, for instance, and have it last 5+ years. The other item I urge you to buy here in the states is your veil, jacket, or suit. I’ve ordered items that I knew my kids would use and out-grow from Amazon, but the sizing charts are not sized for Americans. I ended up having to order a XXXL for a 12-year-old, and even then it didn’t fit, and when I tried to return it, the return shipping cost exceeded the cost of the suit in the first place. If you want to try something on, go out to Full Moon. Otherwise, Mann Lake has sizing charts that are really good to use.

Lastly, don’t run out and buy a bunch of expensive honey extracting equipment. Join your local bee club (in the Tallahassee area, it is the Apalachee Beekeepers Association, and South Georgia has the South Georgia Beekeepers Association). Most bee clubs have equipment available to their members to use.

That’s it for this piece. Don’t blow the bank on this adventure. It should be fun and rewarding. Be sure to sign up for our newsletters to keep you abreast of what is happening.

This website uses cookies.

We use cookies to analyze website traffic and optimize your website experience. By accepting our use of cookies, your data will be aggregated with all other user data.